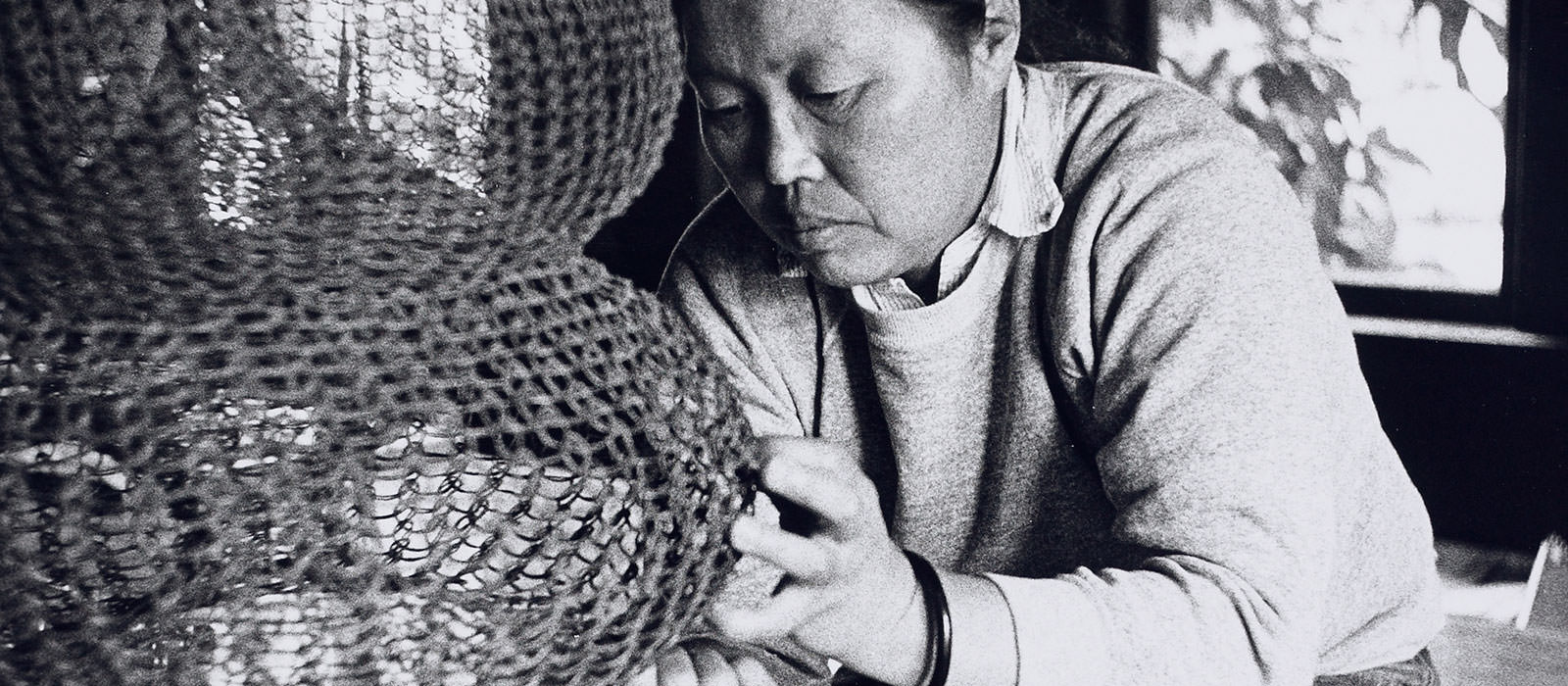

Photo by Allen Nomura

“My curiosity was aroused by the idea of giving structural form to the images in my drawings. These forms come from observing plants, the spiral shell of a snail, seeing light through insect wings, watching spiders repair their webs in the early morning, and seeing the sun through the droplets of water suspended from the tips of pine needles while watering my garden.”

Looped-Wire Sculpture

In 1954, Asawa was asked to explain her work for her first show at the Peridot Gallery in New York. What set her work apart from others making sculpture then was their lightness and transparency, as well as their movement since they were suspended from the ceiling. She wrote, “A woven mesh not unlike medieval mail. A continuous piece of wire, forms envelop inner forms, yet all forms are visible (transparent). The shadow will reveal an exact image of the object.” It was only much later in life that she realized that she had made the same forms as a young child on her parents’ farm. Sitting on the back of a horse-drawn leveler, which scraped the soil so that irrigation water could reach the end of the rows, she dragged her toes in the fine soil as the horses walked to make the playful and complex biomorphic outlines of her looped wire sculptures.

Tied-Wire Sculpture

“I started in 1962 when a friend of ours brought a desert plant from Death Valley and said, ‘Here’s something for you to draw.’ I tried to draw it, but it was such a tangle that I had to construct it in wire in order to draw it. And then I got the idea that I could use it as a way to work in wire. I began to see all the possibilities: opening up the center and then making it flat on the wall, and putting it on a stand.”

Asawa often describes these tied-wired sculptures using terms such as “tree” and “branching form.” She began with a center stem of 200 to 1,000 wires, which she then divided into branches using nature as her model. As she continued working in this form, she moved into more abstract forms using geometric centers of four, five, six, and seven points. If you look at these sculptures, you can see how the number of points in the center defines the forms that the branches take. As with her other work, these tied wire forms gave her the freedom to explore how “the relation between outside and inside was interdependent, integral.”

Electroplated Sculpture

Beginning in the mid-1950s, Asawa sought advice on how best to clean her looped-wire sculptures from industrial plating companies in San Francisco. The brass, iron, and copper were beginning to tarnish and oxidize. A couple of businesses dismissed her request to clean sculptures as not worth their effort. But she finally found C&M Plating Works, where Carl and Mac “took pity on me and were willing to try new things.” They helped her experiment with cleaning methods and patinas. On a trip to the platers in the early 1960s, Asawa noticed some crusty copper bars in the plating tank, the byproduct of a process that smoothed the chrome for car bumpers. She admired their gritty texture and green patina. She asked Mac to help her figure out how to get the same texture and color on her tied wire sculptures. Through trial and error, they reversed the electroplating process. After she formed the sculpture in copper wire, it remained in a chemical tank for months, where it grew layers of rough, green and colorful textured skin similar to coral or bark.

Cast Sculpture

“…I am fascinated by the possibilities of transforming cold metal into shapes that emulate living organic forms.”

Asawa began experimenting with cast forms in the mid 1960s. For her first public commission in San Francisco, the Andrea mermaid fountain at Ghirardelli Square, she had to design the mermaid’s tail. Her solution was to first loop it in wire, then dip it in wax, and then cast it in bronze. She enjoyed working with the foundrymen at the San Francisco Art Foundry, and she was captivated by how she could take an idea from one material, add to it with wax, have it invested or made into a mold, and then see it transformed into bronze. She did this with wire, paper, baker’s clay, even persimmon stems. Her cast sculptures reaffirmed what she learned from her teacher Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, “The artist must discover the uniqueness and integrity of the material.”