Ruth (back row, far right) with friends at Rohwer Relocation Center, 1943.

In the hysteria following the outbreak of the World War II, the United States government feared that Japanese Americans would commit acts of sabotage against their country. Although no such act was ever committed by a Japanese American, some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in the Western United States were removed from their homes and made to live in incarceration camps. Of these, almost 80,000 were United States citizens; 40,000 were children. Ruth Asawa was one of these citizen children.

In February 1942, Ruth’s father Umakichi, a 60 year-old farmer who had been living in the United States for forty years, was arrested by FBI agents and taken to a camp in New Mexico. The family did not see him for almost two years. In April, Ruth was sent along with her mother and five siblings to the Santa Anita race track in Arcadia, California, where they lived for five months in two horse stalls. They took only what they could carry. “The stench was horrible,” she recalled. “The smell of horse dung never left the place the entire time we were there.”

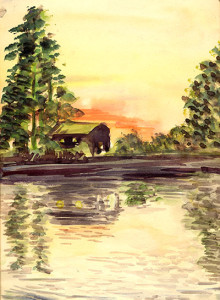

Asawa’s On the Bayou (WC.309), 1943

Suddenly Ruth did not have to work long hours on the family farm, and she used her free time to draw. Among the detainees were animators from the Walt Disney Studios, who taught art in the grandstands of the race track. In September, the Asawa family was sent by train to an incarceration camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, where Ruth continued to spend most of her free time painting and drawing.

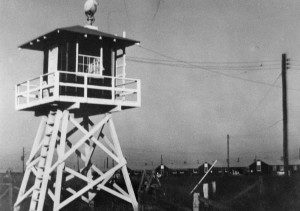

Guard tower at Rohwer Relocation Center. Photo courtesy of the National Japanese American Historical Society

The Rohwer Relocation Center, surrounded by eight watch towers and barbed wire fences, held eight thousand Japanese Americans. It was built next to a swamp of cypress trees.

“There were lines for everything,” Ruth recalled. “I believe half of our time there was spent waiting in line.” The water was hard to get used to. “It smelled like rotten eggs. The only way it was halfway palatable was to boil it and make tea.” The Asawa family lived in a tar-paper barracks in Block 13.

Detainees behind the fence at Rohwer Relocation Center. Photo courtesy of the National Japanese American Historical Society.

Ruth’s identity card that allowed her to leave the camp. It is now part of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery collection.

Ruth was fortunate because her period of incarceration lasted only sixteen months. A Quaker organization called the Japanese American Student Relocation Council gave her a scholarship to attend college in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

In August 1943, she was issued an identification card by the War Relocation Authority that permitted her to travel to Milwaukee. Her high school English teacher from Rohwer, Mrs. William Beasley, drove her to the train station. She told Ruth, “This is a terrible thing my government has done to your people. Don’t look back on your life here. You must go on.” She did not see her parents again until September 1945, shortly before they were released in November of the same year.

For many Japanese Americans, the upheaval of losing everything, most importantly their right to freedom and a private, family life, caused irreparable harm. For Ruth, the incarceration was the first step on a journey to a world of art that profoundly changed who she was and what she thought was possible in life. In 1994, when she was 68 years old, she reflected on the experience:

“I hold no hostilities for what happened; I blame no one. Sometimes good comes through adversity. I would not be who I am today had it not been for the Internment, and I like who I am.”

Mrs. Beasley, the beloved English teacher, is shown standing. Ruth is seated second from the left. Art teacher Mabel Rose Jamison took this photo.